Variation IV: Debussy’s Pagodes from Estampes

Debussy brought the concept of touch and color to a new level. In an unprecedented way, the tone colors begin to take on as much importance as the notes and dynamics themselves; painting the music is now as important as singing it, often even more so. The subject, as in most French Art of the period, has a warm but veiled, indirect quality.

Debussy is as much a revolutionary as Beethoven. He turned an approach to harmony and form developed over centuries completely on its head, showing the beauty and validity of viewing them through Alice’s Looking-Glass. Many of the same harmonic colors of his colleagues and predecessors, seen through this magical lens, take on opposite qualities. Debussy’s Theory and Composition teachers at the Conservatoire knew that his experiments could only be the revolutionary lunacy of an overzealous youth, but his early efforts, including his masterpiece, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, proved them wrong. They and their successors scrambled, groping for new definitions and justifications. Like most acts of genius, the theory came after the fact.

Parallel to the harmonic developments taking place not only in Debussy’s music, but everywhere, the science of orchestration was reaching ever new heights. The orchestra was already quite well defined by Beethoven’s time – even Mozart’s for that matter – but in the second half of the 19th century, it began to reach maturity. It would keep expanding until WWI, when the economic situation, a lack of musicians and general shock would bring composers back to a more minimalistic approach regarding orchestration.

The developing orchestra taught composers about sound potential; the great orchestrators, from Beethoven to Berlioz, Wagner to Rimsky-Korsakov, Debussy and Ravel, taught the orchestra what it could do. Although Liszt was the first great orchestrator of the piano, Debussy brought the notion of orchestral color for color’s sake to a new level at the piano. He wrote for the piano with the colors of the orchestra, but in a completely pianistic way. Liszt expanded the piano’s possibilities by refusing to accept its limitations, breaking strings left and right along the way; Debussy understood the limitations of the piano, accepted them, and discovered how to seemingly transcend them.

One of the paradoxes of interpretation is that the French School of interpretation has little to do with French Music. (The Italian School of pianism is another – it has absolutely nothing to do with the Italian’s love of Opera.) It’s as if interpreters have set up a mode of thought in opposition to their composers, to somehow to prove their independence and superiority.

{Allow me a small digression. During the second half of the 19th century, performers slowly stopped composing, and composers stopped performing. The world of Music was becoming ever specialized. The Renaissance Man, as it were, was becoming a thing of the past. Composers, for a time idolized, lost their place to Performers. And into the 20th century, mere Performers lost their place to Conductors. Broadness in Music Education was replaced increasingly by a race to reach the top as fast as possible. This approach remains to the present day. Is this Progress?}

French interpretation, even now, is characterized by clarity and dryness. The clarity of course makes sense, as does, on a certain level, the avoidance of extremes. But remember that little music is more extreme then Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique. And Berlioz wrote in his classic orchestration manual that the ideal symphony orchestra of the future would consist of more than a thousand performers . . .! The father of modern Orchestration had an insatiable desire for extreme contrast. How seemingly un-French!

Ravel, in his Gaspard de la nuit, wrote that he had set out to write a caricature of Romanticism, but that in the end, Romanticism seemed to have gotten the better of him. The insane contrasts couldn’t be more extreme. The perceived limits of the piano and the pianist are not respected! He somehow manages to surpass even the demands of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes. This from a Frenchman. Never underestimate the French, as French interpreters do consistently.

Where does the French School’s love of dryness come from? French composers of the late 19th and early 20th century expanded the concept of Pedaling into an Art-form in its own right. They perceived its transformational, magical powers and used them to build up layer upon layer of enveloping harmonies, subtly mixing forbidden colors. Yet the French School abstains as much as possible from the pedal, as if it were dirty and profane. It’s no wonder that it took a foreigner, and a German at that, to first realize the nuances of the French impressionists – Walter Gieseking. And he would pass on the mantle to another foreigner, the Italian Arturo Benedetto Michelangeli, to continue the French tradition. They say it takes a foreigner’s eyes to understand what’s unique about a country, and certainly this has been the case with French interpretation.

Debussy’s Piano works are touch Etudes. Each is a study in balancing contrasting colors in a tight space – very few notes, each packed with meaning and absolute individuality. Each piece requires the self-control of a Mozart specialist and the technical prowess of a super-virtuoso. The technical feats are often enormous, while seeming understated, and like in Mozart or Beethoven, a single note out of place often destroys the entire effect.

But don’t be led astray – just because there’s more of an emphasis on tone-color than before, the three other pillars of interpretation – Song, Dance and Architecture – are still very much alive and active. Interpreters of Debussy most often forget to sing and dance! Realize what’s special about this music without exaggerating it.

In 1903, nine years after his early symphonic masterwork, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and two years after his Operatic masterpiece, Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy composed one of his most beloved piano suites, Estampes. The first movement is an ode to the orient, Pagodes. We will examine its first eight bars.

The Pagoda is a five-sided edifice consisting of several levels. The base is generally very simple, and each level becomes increasingly ornate. Debussy depicts this architectural concept sonically with simple gongs in the bass, slightly more flowing accompaniment in the Tenor and Alto, decorative melodic writing in the Soprano, and fast-moving glissando-like movement when he later reaches into the heights of the keyboard.

Defining the Color Levels

Sometimes you’ll come across examples where the chorale-like texture is either absent or less evident. Usually, though, you’ll discover it hidden just beneath the surface. In choral music and orchestral music, parts often divide within sections. In Debussy’s orchestrations, in part inspired by Berlioz, he sometimes divides sections into four or more parts, such as four Clarinets forming a four-part harmony.

The first measure of Pagodes has seven layers, the third, nine. See if you can define how the Bass, Tenor, and Alto parts divide.

Here are the first four bars of our excerpt color-coded:

As you practice separating the four primary levels from one another, try to grade the color within each part, at least dynamically. Notice the slight gradations of hue, horizontally and vertically, within this possible realization of the third bar alone:

The colors shimmer, dancing and singing!

Creating an Orchestral Sonority – Applying Vertical Hierarchy

Apply Vertical Hierarchy to the example in an exaggerated way. When chords line up vertically between the hands, play the right before the left. Once a wide spread becomes comfortable, narrow it to a barely discernable level. Here are the first four bars:

Now apply Reverse Hierarchy, as if arranged for a Harp Duo, every chord rolled within each hand from bottom to top. Exaggerate the rotation in the forearms from the elbow. Enjoy the richness of the harmony and the freedom of a large spread. Once this becomes comfortable, narrow the spread so that it sounds almost perfectly lined up.

Next, apply Free Placement, becoming more aware of Time-dimensions, how anticipating or delaying entries changes the character and meaning of each line. Make the spread as wide as possible at first, then narrow it until it feels stylishly convincing. The spread in Debussy can remain rather wide, as long it feels passive and orchestral. If it sounds romantically willful, it’s probably out of character. Exceptions to this are neo-romantic invocations, such as in most of the melodic content of La soirée dans Grenade, for example, or romantic caricatures, as in the Tristan quote from Golliwogg’s Cakewalk (from Children’s Corner), marked maliciously, avec une grande émotion.

Give some thought to how you’re packaging chords. Remember that it’s often quite effective to play the outside of chords before the inside, like so:

Notice that virtually every note respects Vertical Hierarchy. As I set up the eternal feel of these opening bars, I don’t want anything to stand out obviously, rhythmically or sonically.

Establishing Horizontal Hierarchy

Debussy was first introduced to Javanese Gamelan music at World Exposition in Paris in 1889. Westerners are generally struck by the relatively static, uniform beauty of the Gamelan. It’s essentially a Talea Art-form. The language is not based so much on the Westerner’s approach to phrases as it is on building complex patterns of rhythm, pitch and timbre. Still, great Gamelan ensembles can phrase with subtlety and scope not unlike Western Classical phrasing. The energy patterns can be analyzed with the same ease and fluency of virtually all Western Music and of all spoken languages.

There’s no way of knowing what kind of performances Debussy heard, but he began using pentatonic modes extensively from then on, and in Pagodes, he managed to extract the true essence of Gamelan music while melding it to Classical phrasing and harmony.

Identify the Energy Pillars in the eight-bar excerpt. First define the smaller phrase units and the Energy Pillar within each of them, and then notice how the phrases group together and how the Pillars balance and contrast one another.

Realize your Pillar map, exaggerating each of them with a big accent or sforzando, then play naturally, letting the Pillars guide you and lead you. Make adjustments to them as necessary. You’ll discover that in an excerpt like this with rather static harmonic movement, the underlying dance movements of the meter and rhythmic patterns will help you define the pillars and surrounding gestures.

Applying and Removing Gloss

Just as Debussy has placed Eastern pentatonic harmony above a Western tonal setting, not every tone color in Pagodes represents those of the Gamelan – ringing gongs and metal plates are balanced by mellower, warmer, more Western sounds. The finish as well displays the whole gamut, from high gloss to flat matte. The Gamelan sits on top, in the treble, with the more rounded colors in the lower inner textures.

Even where Debussy represents the Gamelan directly, he does so in a rounded or veiled way, as Renoir or Monet might have depicted them performing. Although Debussy disliked being labeled an “Impressionist”, there’s no denying the similarity between his works and the Impressionist Artists. (Even for a revolutionary and a visionary, it’s hard to completely escape your culture and your generation.)

As you clarify the relative levels of Gloss, ask yourself which technique is the most appropriate to achieve the specific type of Gloss you desire. Do you require a faster attack, a higher attack, a more brilliant mallet, a more compressed sound? Experiment extensively and define your choices as specifically as you can.

Defining the Pedaling

Debussy is the third of the three pedal liberators, preceded by Beethoven and his pupil’s pupil, Liszt. Gamelan, essentially a pedaled Art-form with its ringing metal chimes and gongs, finds an ideal translator in Debussy.

The sustaining pedal, only occasionally surfaces completely in this four-and-a-half-minute work. It begins with the pedal fully depressed. Inside that outer 10% layer of watery haze, the pedal operates in much the same way as it would for any other work. The tricky part in Debussy and Ravel is to maintain the long notes while subtly grading and clearing the local texture. Debussy often requires low bass notes, as in our excerpt, to ring for several measures; the uninitiated might infer that the pedal should be left floored, but this makes for a muddy texture.

Debussy forces you to attain a virtuoso right foot, as well as ultra-sensitive ears to overtones and undertones. After working out the pedaling of a work of Debussy or Ravel, any other repertoire you approach will have matured in terms of its pedaling and sound.

Play through the eight-bar excerpt, being aware of your pedaling choices, not only where you consciously change it, but every miniscule gradation. Write your pedaling into the score with as much precision as possible, trying to achieve at least ten depth-levels of pedal. Rid your mind of the idea of the pedal as a vertical tool – it paints beautiful, long, detailed mountainous and cavernous landscapes. Because the pedal can never be used outside the framework of time, it is ever horizontal.

Here’s my pedaling of the first four bars of our excerpt:

I begin with a slowly descending pedal over the first beat. This allows for a clear initial attack and helps differentiate the colors and overtones of the first two open-fifth gongs. Visually and sonically, it conjures up a slow descent into a distant realm. I then let it rest fully depressed for a beat and a half, soaking in the oriental perfumes. The third chord, just after the third beat, is an ondine-like spray that beckons a clearing of the air just afterwards, so I slowly raise the pedal over the last beat and a half of the first measure to 50%. Don’t venture further than this or the listener may be jolted by too clean a texture.

Immediately after the downbeat of the attack of m. 2, I descend quickly to 100% again to recapture the simple fullness of the open-fifth fundamental gong, and then immediately begin raising the pedal until about beat 3 to nearly 10%. This slow change of depth over beats 1 and 2 has a similar but opposite of the pedaling in the same beats of the first bar. (This is effective, of course, only if you hold both of these chords in your fingers.) I then descend very rapidly to 100% again for the ondine splash, after which I again raise the pedal slowly to make the colors purer and leaner.

On the downbeat of m. 3, I come up to 100% for my first quick breath of fresh air. This is possible by giving extra presence to the open-fifth chord, which briefly distracts the ear from the loss of overtone haze. I then plunge immediately to 100% and let it rest there at the ocean floor for nearly two full beats, and then let it ever-so-slowly rise up to 70% by the attack of the downbeat of m. 4, after which it plunges again to 100%.

The last pedaling is perhaps the most interesting. Over 3 ½ beats, it slowly rises to around 50%, creating the effect of a mist burning off in the morning sun. Notice the sharp ascent just after the attack of the final l.h. eighth-note, preparing another delicate gasp of air on the following downbeat.

A word of warning as realize my pedalings and create your own: when making even minor adjustments, take care not to lose the fundamental tones and overtones of the long notes (as it’s not possible to hold them in the hand, their sustenance depends on the pedal) or clear away too much of the combined overtones or do so too obviously as to kill the mood.

Debussy indicates that an occasional use of the Una Corda Pedal (2 Péd.). The soft pedal is one of the least dependable aspects of the modern Piano. Often it’s called for when it’s not really necessary or appropriate. It can usually be as effectively realized by changing the mallet, dynamic, and/or energy of the stroke. The effect should always be respected, but not blindly.

The soft pedal is as often abused as the damper pedal, even more so. It’s the friend of the unskilled, the fearful and the shy. I’ve seen countless concerts where the left foot was glued to the soft pedal the entire evening, depressed partly or fully for minutes at a time.

Only use the soft pedal for very special, calculated effects, not as a cover-up or a security blanket. Check your effects on the Piano in the hall before the performance to make sure you can get the effect you seek. As a rule, be prepared to achieve every effect you want without the soft pedal, and only move your left foot to the soft pedal when you intend to use it. You’ll be more physically balanced if your left foot is farther back.

Linking and Separating

Linking and Separating involves Pedaling, Rubato, Color Differention, and Dynamic Delineation. However, its most important aspect is Energy organization and purification. I usually begin with the smaller gestures and move outwards into larger gestures. One of the most common problems I deal with as a vocal coach is singers trying to make a long phrase without acknowledging its inner gestures. If you seek the noble, arching gesture, don’t think it can be achieved with a bulldozer. As you purify and tighten the small gestures, the larger ones often come of their own.

I find that gypsy-izing rhythms heightens their innate qualities and tightens small gestures mentally, emotionally and physically. Simply make the short notes shorter and the long notes longer, such that the short notes feel more like grace notes. Within each compressed rhythmic unit, don’t allow in any unnecessary energy.

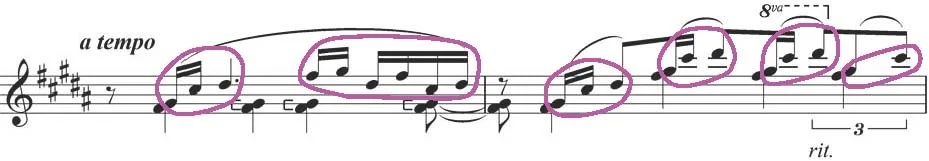

Here are the third and fourth measures of our excerpt with the smallest gestures in the r.h. circled:

Play all of the sixteenth notes very quickly, as grace-notes. After compressing the individual gestures like this, play them again normally and naturally and you’ll discover that the energy has less static and flows more effortlessly.

Next, group small gestures into larger ones, in twos, threes or fours, so that the point where the energy turns is focused and refined.

The first turning point in the third measure comes on the third beat, here marked by a dotted line:

It’s very easy to let the energy at a turning point become static or harden into a mental, emotional wall; the energy must remain fluid. To break this wall, or keep it from ever forming, it helps to rush the tempo around the turning point. This forces the linking energy to become more concentrated and malleable. Play it again naturally, without rushing, and you’ll discover that the gestures link and separate more clearly and effortlessly.

After the underlying energy skeleton has been thus solidified, work through the other main aspects of Linking and Separating – Pedaling, Rubato, Color Differentiation, and Dynamic Delineation.

Defining Rubato

One of the defining features of Gamelan music is its steady, flowing rhythm. Debussy, on the other hand, defines his textures by the fluidity of the beat. It’s no accident that his orchestral masterwork depicts the ocean. Still, Debussy uses a fairly steady beat when it serves his purposes. In our excerpt, you should try to achieve the affect of a steadily flowing, timeless beat that breathes and is never pushed. Within this definition lies a great deal of leeway.

Play it through noticing all of the tiny liberties you take. Try notating them with forward and backward arrows in your score. When the tempo remains steady, even for only a beat or two, there are no arrows.

Don’t confuse straight Rubato arrows with arched Direction arrows. The concepts are quite different, although they often convene. It’s when they don’t match, or even run opposite one another, that I find most fascinating. It’s similar to Direction as it relates to crescendo and diminuendo – it’s more common when forward motion parallels crescendo and backwards motion diminuendo, but music often demands otherwise. Many phrases lead into an intimate or reserved climax in diminuendo (yet it should be noted that few phrases taper in crescendo…).

Often, to make an important statement or arrive at the climax of a phrase requires extra time – backwards motion – yet forward Direction. Arriving to an Energy Pillar, again, usually happens in some form of crescendo, but occasionally in diminuendo.

Here are the first four bars of our excerpt with Rubato arrows and Direction arrows:

It’s tempting in a piece like this to be drawn in by the lotus floating in the water surrounding the Pagoda, and play in a continuous ritardando, always on the back side of the beat. This may make the work feel timeless to you as you play it, but I can assure you that the audience will feel it instead as endless. For every flower you smell, breeze by seven or eight. Thus, if you choose to savor the first three notes of the Soprano melody in bar three, even ever so slightly, let the rest of the phrase float along with less importance, carried on the wind. This is true of virtually every ritardando as well – when it’s over, move forward boldly and immediately!

In bar seven, the same Soprano melody of bar three is overshadowed by a new melancholic melody in the Tenor. I allow these two measures (as well as mm. 9-10, outside our excerpt) to be slightly slower in tempo in order to let them speak out seriously, but then I immediately take back tempo in bar eleven, restoring the equilibrium. These are minor variations in tempo that the listener will feel but not notice. The interpreter on the other hand needs to become aware of even the most miniscule alterations of tempo so as to be able to manipulate them and not exaggerate them. An occasional check against the metronome may increase awareness of your effects.

Remember that Placement, whether Free Placement, Vertical Hierarchy or Reverse Hierarchy, is the second aspect of Rubato and Tempo Modification the third. Mastering Rubato means mastering each of the three individually and then mastering how they combine. Timing is of the essence! So often, everything seems to line up perfectly but the effect fails to reach the listener – the problem might very well be that it was simply poorly timed.

One of my teachers took a hard-line on poor timing – If you play one note late, the rest of the notes in the entire composition will be late! I thought him a madman at the time, but sometimes it really does have that effect. You can lose the listener by drawing out a phrase or section too long. He begins to daydream, and by the time he wanders back, he’s lost the thread and the entire performance has become meaningless.

Differentiating the Texture of Touches

There are many ways to approach the Talea in the excerpt, depending largely on how literally you wish to depict the sound of a real Gamelan orchestra. The root of the word gamelan means hammer – should it be represented as such or be allowed to be transformed? The Piano itself is not unlike a Gamelan ensemble.

Debussy is very specific about touch, giving every note a rather precise touch indication regarding dynamics, articulation, and phrasing. Yet the pedaling is left up to the player, and the demands of the notes themselves regarding pedal length usually imply long pedals.

This brings us to the heart of Wet Talea – when the pedal is depressed, are you required to make an effort with your fingers to respect the touch indications, or is it enough for those indications to simply sound as notated? The answer would seem simple, but since Debussy has already implied that the pedal be depressed for long stretches, do his articulation marks apply to the actual desired sound, or to a certain type of finger touch within the pedal?

The answer is elusive. When do his slurs refer only to phrasing, when to legato, and when to both? Let’s examine the score for a moment. In the first measure, the first chord cannot be held longer than about two beats as notated because the l.h. then needs to pass over the r.h. to play the third chord on the and of the second beat. Should it be released to the pedal immediately, or after a beat or two? I play it as a Gong, released immediately to ring in the pedal. The second chord could be held in the fingers for the full duration – should it be held with the fingers or released to the pedal that Debussy clearly intends by the whole-note chord on the downbeat, which cannot be held in the fingers? I play it like the first, releasing it immediately to the pedal.

Now in the second half of the first bar, we have our first slur, implying a legato phrase. Above the top G-sharp, he places a tenuto mark, implying that it should be held in the finger, at least long enough for the effect of tenuto to enter the sound. To play these three chords with a real finger legato, crossing hands in tempo, would be awkward, although playable. I doubt he intends them that way, but I do think he intends them to sound smooth, connected, and somewhat melodic.

The third measure presents a more pressing question: should the slurred r.h. melody be played with a finger-legato or simply sound legato? It’s easy to hear it as a Gamelan melody, hammered out as on a Xylophone or Marimba, yet if Debussy wanted that, would he not have written a staccato mark over each of the notes, or written martellé? None of these are obvious choices. Personally, I try to achieve the individuality of each attack with a non legato touch (and pointed mallets), while respecting the legato intentions by thinking legato and letting the pedal to the actual connecting.

Each interpreter has to come to his own conclusions as to how to interpret Debussy’s intricate but sometimes cryptic interpretive indications.

Play through the excerpt becoming aware of your own Talea choices. Are you achieving contrast between layers and within layers? Are you aware of how you’re releasing notes, varying the speed? Mentally notate the length percentage of each note and the speed of its release. Experiment with various possibilities, then rework your intentions and realize them.

The Dry Pedal – Finger-pedaling

Dry Debussy doesn’t quite exist, yet Dry Pedal still plays a very important part in Debussy, and precisely because such constant veiling in the pedal is required. The texture must always remain crystal clear, never muddy or murky. This can only be achieved with subtle pedalings within pedalings, without ever losing the notes that count most. Many highlighting pedals required a good and wet Dry Pedal underneath to make the effect realistic.

Take away the pedal completely and see how closely you can achieve your pedaled intentions without pedal. Only when you become comfortable without pedal should you begin adding it in again. Notice the added dimensions your playing takes on.

Relax the finger-pedaling, striking a balance between normal playing, and finger-pedaled playing. Now try to think of the finger-pedal in the same way as the sustaining pedal. Imagine that you can depress it 10%, 20%, 50%, 100%, at any given time, depending on the effect desired. Sometimes the real pedal and the dry pedal will work in parallel, but more often they will contrast one another, creating effects that could be achieved no other way. A multitude of effects are now at your disposal.

From the Key Surface or From the Air?

Debussy seems to have taught students to play from the key-surface. Whether he meant this for only certain effects or as a constant is hard to determine. Let’s say he meant it as a constant – should his wishes be respected? Where does composition end and interpretation begin?

Interpreters and composers would likely have widely varying opinions about this. Remember that composers are rarely the best interpreters of their own works. Often interpretation marks they’ve put into their scores represent their own inferior interpretational skills. Blasphemous! And seemingly impossible, yet so.

How could a composer not be the best interpreter of his own works? And I don’t simply mean best performer, as if the only reason he fails to be the best interpreter is because of a flawed technique or a personality that doesn’t lend itself to the stage. I’m speaking on a much more basic level. Penetration of a score is a separate Art-form from its construction. Composition is not an abstract Art-form – it’s linked to the means of performance, to the specific techniques of the instrument for which it’s composed or arranged. A composer is often capable of crossing the bridge separating composition and interpretation, completing the entire journey. But composition doesn’t require the composer to be able to successfully cross the bridge, either virtually or practically, and certainly not on a superior level.

Because this real gap exists, composers often make mistakes in interpretational indications in their scores. A composer’s less-than-ideal understanding of an instrument may not allow him to write ideally for it. Is it unreasonable to imagine that a great interpreter might be able to improve upon a score, in terms of interpretational markings, and even perhaps occasionally upon the notes themselves? I leave this to your consideration.

As you consider Height’s vertical and horizontal applications in light of Debussy’s views on Piano Technique, know that you’re justified in using Height however you like, in order to serve your interpretation of the work.

Height is one of the primary ways to achieve Gloss. Height without Depth creates a delicate, precise, somewhat superficial sound, a color that works beautifully throughout Pagodes. Experiment on your own with constantly varying Height levels to achieve a convincing interpretation. Play from the key and from inside the key for contrast.

Experiment combining Height with the Four Mallets, one at a time, then in various combinations.

To the Key-bottom or Beyond?

Depth might seem the antithesis of a struck, gonged reality, but Depth is simply the following through of a stroke. If you hit a gong, would you stop at the surface, or round out, letting the gong absorb your weight?

Explore the possibilities of Depth in our excerpt, letting every note pierce the key-bottom. At first, it may feel heavy or forced, but then it becomes natural and feels lighter in the arm. Once you’ve achieved Depth, you may want to take some of it away, but I doubt you will ban it completely, even from this airy, watery, ringing excerpt.

On Conducting and Studying the Score Away from the Piano

As a child, I took occasional lessons from a Professor who liked taking scores along with him into the mountains on hiking trips. At the time, I thought he was just trying to find an excuse not to do real practice. Pagodes might be better understood in such a setting, sitting outside a monastery hidden deep in a mountain forest. Finding unique, inspiring places to study scores can sometimes expand your mind to the possibilities of all that the Art of Piano embraces. Likewise, just as composers take inspiration from Art, Dance, Literature, and Poetry, practice is usually most productive when balanced with a healthy intake of Life, and Art.

My Liszt Sonata is still strangely imbued with The English Patient, which sat on the piano and kept me company during practice breaks while I first studied it seriously.

Imagining Real Orchestration

Listen to Debussy’s La Mer. How would he orchestrate Pagodes? What solo instrument, for example, would take the Soprano melody in measure three? I imagine the Flute, here, echoed two bars later in the same melody by a solo Oboe. In bar seven, I hear a solo Clarinetist, pp, accompanying an English Horn, mp, in the Tenor melody, tenderly, stoically. In the beginning, I give the accompaniment note-for-note to Harp. In the first two bars, I double the Harp in the Basses, divisi, pp, on the low B and F-sharp, and the Cellos, divisi, on the higher B and F-sharp. In measure three, I punctuate the downbeat with a distant gong, ppp, and I divide the Cellos in four to cover all four notes of the l.h. chord, doubling them on four French Horns.

Here is the excerpt orchestrated, all instruments notated in the key of C for easy reading. Instruments usually read an octave or two higher or lower than actually written, such as Double Bass, Piccolo or Glockenspiel, are notated as well as they sound. The only clef other than the bass or treble clefs is the alto clef, for Viola. This is all meant to help less experienced full score readers.

Mine is but a simple sketch to inspire you to imagine your own orchestration. Read through the score several times, internalizing it and singing the parts. Now begin conducting it, as you continue singing along. It’s in a simple 4/4 (down, left, right, up) with no real subdivisions, so it doesn’t present any serious problems from a technical point of view.

Simply begin by envisioning your Debussian Orchestra around you. How are the Strings seated? Where are the Winds, French Horns, Brass, Percussion, Harp? Who’s first chair in each section? Once you’ve located everyone, invite their attention, raising your arms embracingly, breathe, give a simple, precise, predictable, upbeat to the Basses and Gong, and you’re off.

At first, use only the right hand, cueing the soloists simply with eye contact a beat before each enters.

Once you’ve conducted your way through it several times and have developed a clearer mental hearing of it, bring the score to the keyboard and transcribe it into

your fingers as realistically as possible. This is a strict orchestral reduction, meaning that I’ve limited myself only to the notes in the original Piano version. So as you re-transcribe the orchestral version for solo Piano, you’ll simply be playing the original notes, but try to show the specific colors of the orchestration.

What changes would you make to my orchestration? Make any changes you like and continue orchestrating the following six bars (mm. 9-14), then work through the same process again.

The Four Principle Mallets and the Four Physical Levels

Play through the excerpt focusing on which mallets you’re using. Is there room for improvement? Experiment. Debussy adapts particularly well to the sides of the fingers and the fingernails. Gong sounds can be realized with the bone on the outer side of the first joint of the thumb. Penetrating Horn-like sounds work well with the pointed tip of the thumb, just beneath the nail, supported by the second finger.

The Four Physical Levels are essentially an extension of the Mallets; they put the mallets in motion and back them up.

Work through the excerpt focusing only on which Physical Levels you’re using for each note. Experiment combining each of the Physical Levels with each of the Mallets throughout the excerpt to become more aware of how they interact, and of the varied color possibilities they offer you. Make adjustments.

Mimicking Masters ~ The Imitation Filters

Be sure to include both Michelangeli and Gieseking here!

The Hand of God – Using Hammers and Chisels

The passive nature of Debussy makes you hesitant to use any force, which can make your energy pathways weak. Also, the pianos and pianissimos need to be solidly connected to the arm. Using Hammers and Chisels for a little while will bring you closer to the music.

Also, remember that a Gamelan Ensemble consists primarily of hammers hitting slabs or sheets of metal. Perhaps Hammers and Chisels are not so out of place.

Is Percussion Beautiful, Zenful?

What could be more Zenful than a Buddhist Gamelan Orchestra? Buddhists often use percussive sounds to pierce the mind, cleanse the soul. They don’t suffer from the same Jane Austenian sense of what’s genteel and appropriate. Open your mind to alternate realities of sound perception.

In Korea, I accompanied my wife to Mass and was shocked to hear the congregation called to prayer several times by a Gonglike sound straight out of a Buddhist Temple. The clash of cultures was beautiful!

Speed, Weight and Compression

Play through the excerpt, observing your choices regarding Speed, Weight and Compression. All three have a place in Debussy, as do all their combinations. Experiment with various possibilities and notate new choices into your score. Realize them.

Now look back through all the previous filters and ask yourself how Speed, Weight and Compression interact with them. Remember that no filter is an island unto itself – they’re all interconnected.

Super-melody

Debussy is nearly as melody-centered as Chopin. Just look at his early works, such as Claire de Lune and Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. The melody should sing out in a clear, natural way. Veiled, but not hidden or watered down.

Etch it out first in a bright f using Hammers and Chisels, then let it return to its normal state. Super-melody is about you – where are you focusing your mind, body and emotions? Prepare yourself to inhabit the same space as your listeners.