This manual is not meant to give you definitive answers or teach you my interpretations – it presents you with ideas and tools to form and renew your own working habits. I hope that as you work through these filters, you will be enlightened by fresh realizations about the potential of the piano but also struggle with the contradictions; quite often, one filter cancels out another. In your final interpretation (which is of course ever subject to growth and revision . . .) you have to choose between individual filters and combinations of filters. This happens largely on a less-than-conscious level, but the more aware you are of your choices and techniques, the more successfully and convincingly you’ll be able to present them.

When using extensive finger-pedaling, your hands will feel glued to the keyboard and the idea of attacking from the air probably won’t occur to you. So you may need to clear your mind of sticky fingers to approach the following argument.

Should I attack from the key-surface, from just above it, or in grand style from several inches above? Attacking from the air was much more common in the Golden Age of Pianism. The aplomb, the massive orchestral effects achieved — where are they now? Why do most Pianists nowadays play everything from within an inch of the key surface? The answer is obvious but perhaps not often enough discussed. As we entered the Recording Age, musicians gradually tried to make their performances note-perfect, to the point of now nearing insanity. Did anyone ever hear a note-perfect Richter performance, a note-perfect Rubinstein performance, Horowitz? Can you imagine Liszt playing note-perfect! These were all risk-takers. Not that they were irresponsible or wonton, but they knew that certain risk levels were acceptable for the greater good of the interpretation.

Any attack from the air has innate risk involved. It’s much easier to miss a 3-pointer than a lay-up. And each has a distinct value. What would basketball be without 3-pointers! Yet that’s what the music world has come to. Let’s hope that as we enter the 21st century, the tide will turn again.

It’s all about the free flow of energy and thought. Something special happens in the psyche when you give yourself permission to fail – this is one of the key points of Zen. Your emotions free up, your mind expands, your body simultaneously relaxes and becomes alive, alert. All of this free energy finds its way into the sound and transmits directly to the listener.

Learn to accept a greater degree of risk in your approach to music making and your language and power will expand. Limits can of course also be positive, but don’t box yourself in so tightly that you can’t breathe and sing.

Learning to play from the air will enormously expand your dynamic range and tonal palette. You simply can’t attain the exact same color from the key-surface as from the air. You can literally feel the life-giving oxygen in the sound when even half-a-centimeter is at play. And dropping from a couple inches away gives yet another distinct color, not to mention greater volume.

Applying Height Vertically

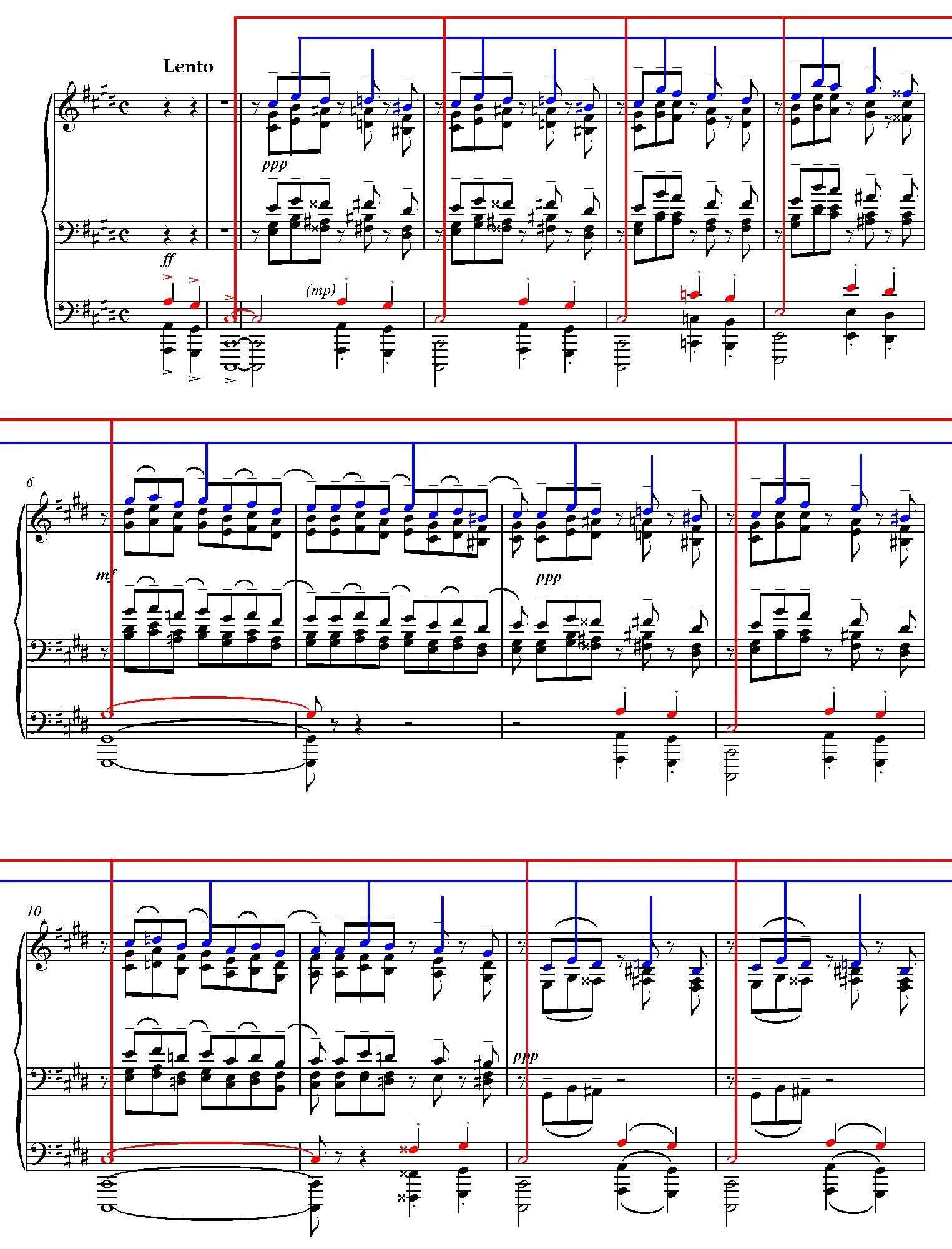

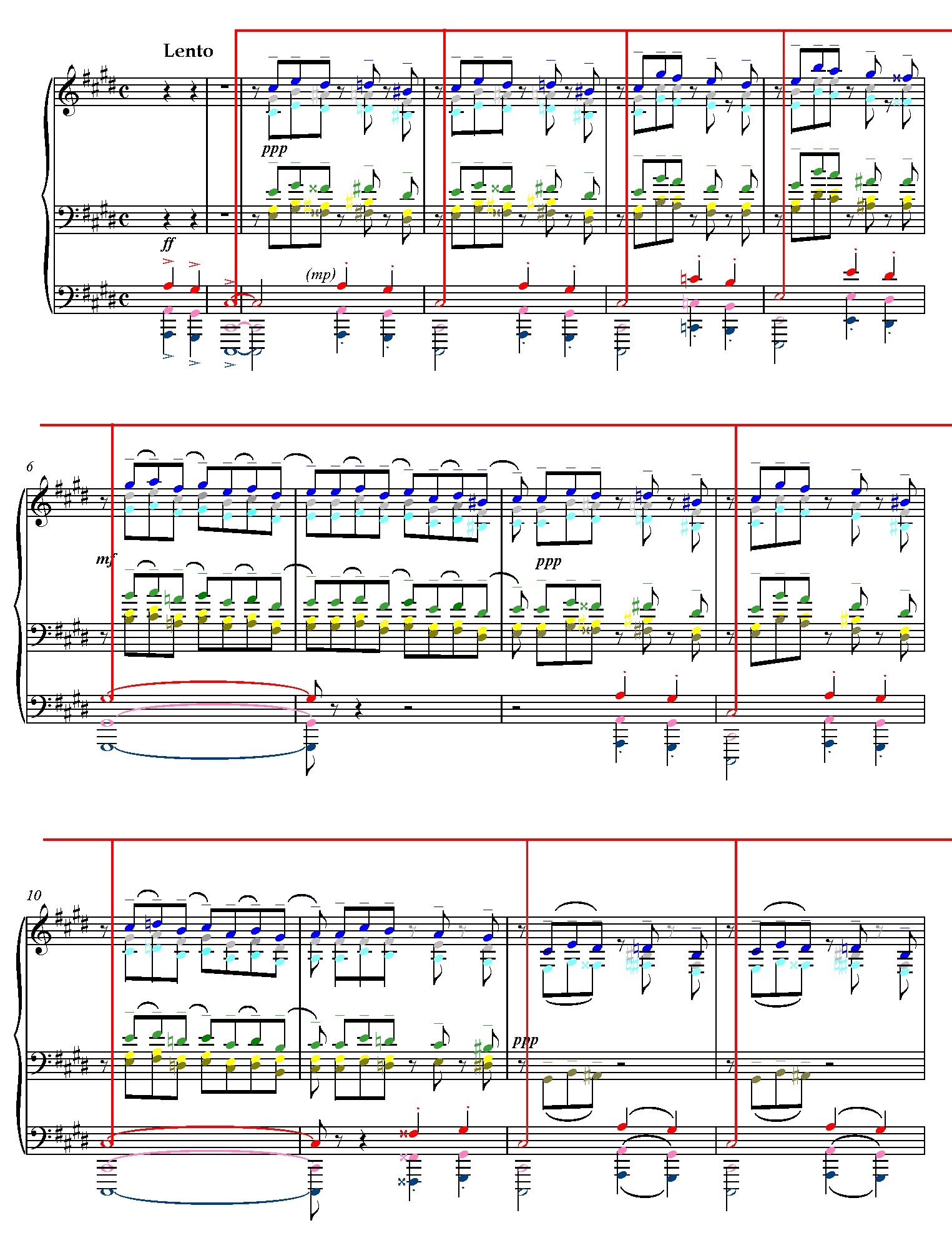

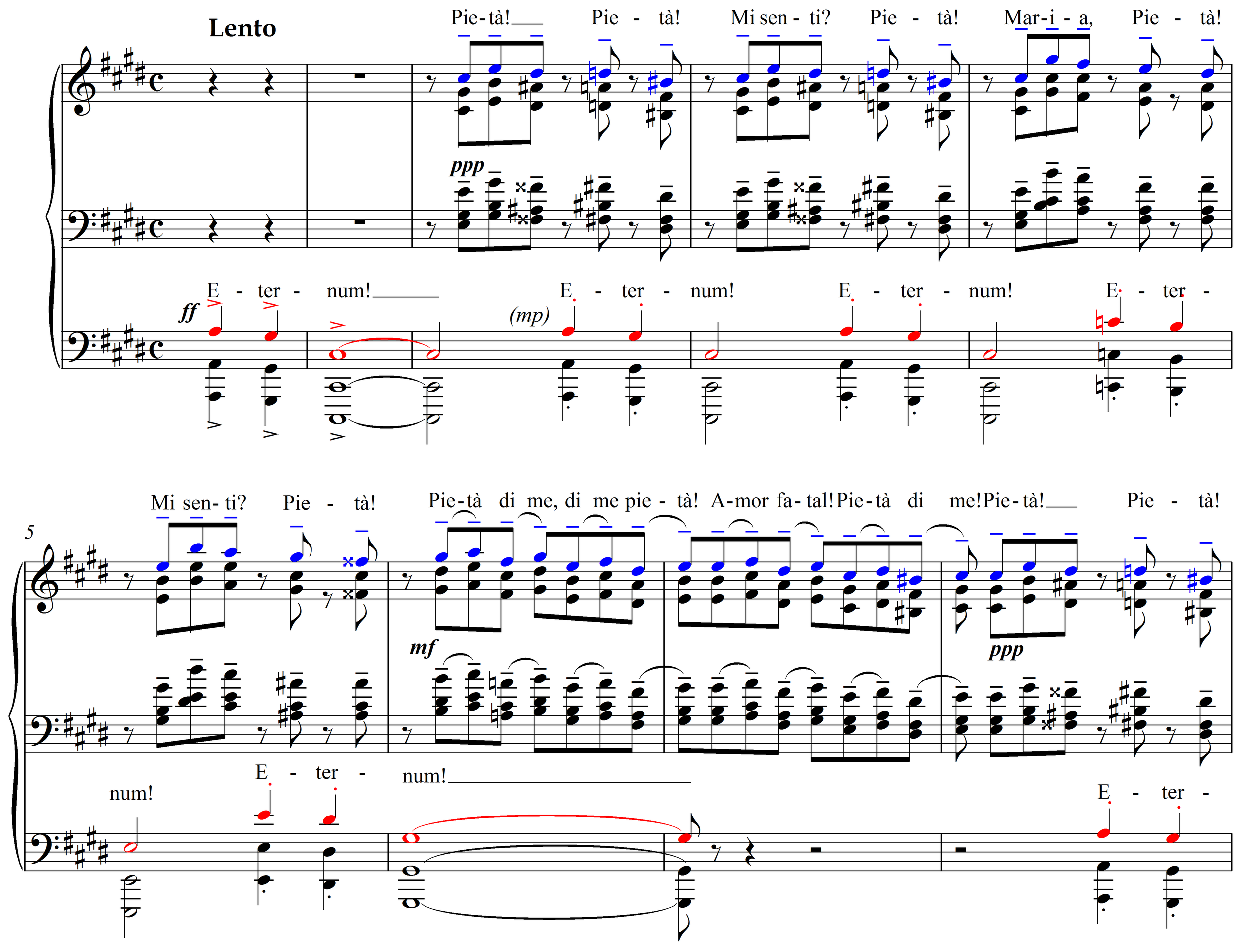

Let’s try experimenting with our Prelude. Try playing everything on the first page from at least a centimeter above the key-surface. An inch or two would be even better, although messier at first. Don’t be discouraged if everything flies out the window and half the notes are split or full-out missed. Try it four or five times. By now you’re probably splitting a much smaller percentage of the notes. Over time and with practice, the feeling of insecurity and enormous distance that even two inches inspires will disappear and you will reclaim your direct connection to the keys.

At first, even as it becomes cleaner, the sound will still be hard-edged and uneven. It takes time to adjust and certain dormant muscles need to be awakened and welcomed into your energy pathways. Gradually, as you gain greater comfort and command, the sound will become rounder and more varied.

You probably feel like your playing for thousands and not simply for yourself in your living room. You can feel the fresh air of the outdoors. There’s the legend of Gottschalk living in Central America up on a mountain with a piano that overlooked the plains below. He would play for the birds and the great expanses. When you let a little oxygen into your sound, you start to feel like you’ve entered the outdoors.

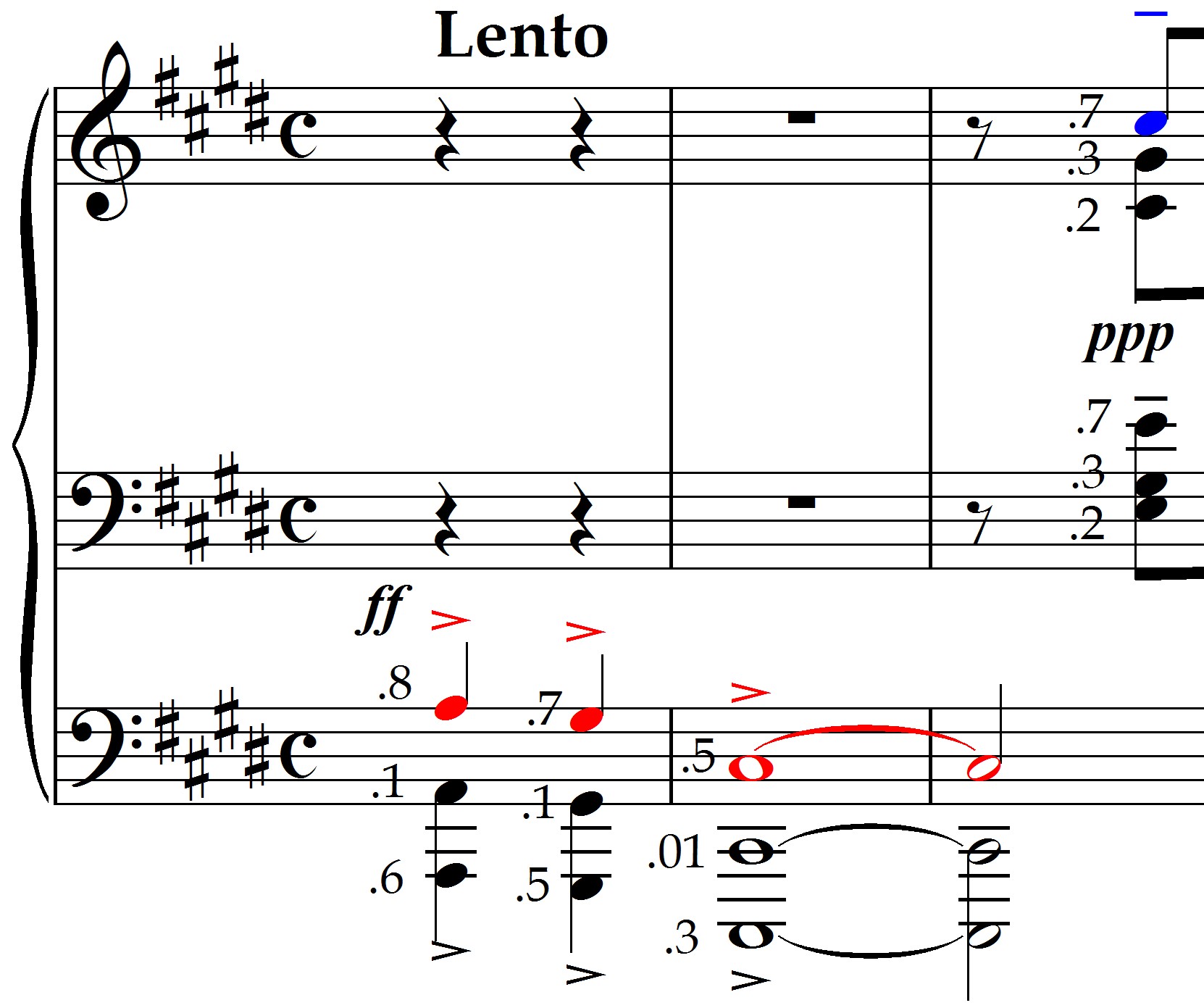

It’s possible to establish orchestral levels simply but varying the height of the attack (just as it’s possible orchestrate based on the depth of the sound, our next chapter). Let’s take first our Red level. Play it from about 2 inches above the key-surface and play the other eight levels from the key-surface.

How does it feel? It should give you the sensation of accompanying a singer at the piano, you being the soloist and the accompanist. This is a powerful language in its own right.

Now try the same technique, but from the Royal Blue level. Because this level is connected in the r.h. to two other levels, they may be brought along for the ride. Later you’ll learn to separate them.

Next, apply the technique to the Dark Green level. Again, because of the two levels connected to it in the l.h., at first you’ll need to bring them along.

Next, try to play the Red level from 2 inches above and the Royal Blue and Dark Green from 1 centimeter above. This will sound more complex and balanced.

Now kick it up a notch. Try the Red level as before from 2 inches, the Royal Blue level from one inch, and the Dark Green level from 1 centimeter. Repeat several times until it becomes comfortable. You should be getting glimpses of glorious sounds.

Work through these steps again now from the beginning, until you begin to feel command over them. Experiment with inserting height into the other color levels, separately at first, and then in various combinations.

Applying Height Horizontally

Like with many other techniques, Height can be applied structurally, either vertically or horizontally. Now let’s examine its horizontal uses. Because Height lends extra definition and usually extra volume to the sound, it’s effective to define horizontal lines by varying the degree of Height.

Let’s explore this concept through our Prelude. Take the first three notes of the Red line. Play the first two notes from the key-surface, but the third, the Energy Pillar, from an inch above the key-surface. Try it a few times until you gain command. Now do it again as you try to remain sensitive to the movement of energy. Can you feel a burst of energy streaming out on the C-sharp? It has added clarity, extra volume, more oxygen, and a very special color in relationship to the other two notes.

Try now playing the entire first page a few times (turn back to the diagram of Red Energy Pillars above) playing all of the Pillar notes from an inch above the key-surface, and the rest from the key-surface. Can you feel the architecture becoming more clearly defined?

Now try to repeat the process ONLY from the Royal Blue line.

Now from Only the Dark Green level.

Next combine the three so that every Pillar (and Secondary Pillar) has a one-inch-above-the-key-surface attack. (Remember that the energy Pillars for the Royal Blue and the Dark Green are identical.)

Now you’re ready to differentiate the levels. Play the Pillars in the Red level (and two supporting levels) from two inches above the key-surface. Play the Pillars of the Royal Blue Level (and two supporting levels) from one inch above the key-surface. And play the Pillars of the Dark level (and two supporting layers) from one centimeter above the key-surface. All other notes should be played from the key-surface.

You’ll need to play the first page several times like this before you begin to have command over it.

If you’ve come this far and you’re willing and capable to take it further, try now isolating the three individual principal Colors (Red, Royal Blue and Dark Green) from their accompanying levels such that the accompanying levels will be played exclusively from the key surface. This in itself is a virtuoso act, but is possible by turning the hands as needed and repositioning the fingers. The Red level, of course, presents no difficulties here because its supporting levels are played by the l.h. Can you hear the colors coming into increased definition and differentiation?

Now let’s approach it from an even more complex proposition. Begin again focusing only on the first three notes of the Red line. Play the first note, A, from an inch above the key-surface, the second note, G-sharp, from a centimeter above the key-surface, and the third note, C-sharp, the first Pillar, from two inches above the key-surface. Try it a few times. Can you hear how dynamic and alive that sounds! Apply the technique to the Red line on the entire first page, any increase in energy or volume echoed by the degree of height of the attack.

Now approach the Royal Blue line in the same way, leaving all other levels flat in our hazy Light Blue.

Now try to combine the Royal Blue (and its five supporting levels) with the Red (with its two supporting levels), without trying for the moment to differentiate them from one another in terms of hierarchy. Try to remain sensitive to the inner energy of both lines at the same time and shape them simply by varying the Height of the attacks.

Now try to play the Red level at a higher general energy level with greater relative Height in the Energy Pillars. If you can manage this while grading and shaping the notes around them, you’re approaching real mastery of Height.

I’ll leave you here with this concept to your own experimentation. But for the most advanced and ambitious among you, I challenge you to take it a step further. It’s possible to employ both approaches to Height – Horizontal and Vertical – at the same time, but it becomes EXTREMELY complex and daunting. Beware: contradictions abound.