The Myth of Evenness

Singers spend their lives learning to sing with a perfect, even legato. Pianists, imitating the ideal of great singing, try to make every note as closely matched to its predecessor as possible. Why is it that few trained musicians arrive at natural phrasing? Why is legato so elusive if it’s so easily defined?

The problem lies in the definition itself. Legato is a paradox because it’s the antithesis of evenness! Two notes side by side with identical color and volume fight against one another like two positive magnets pushed together – they cancel each other out. This truth applies not only to legato but to any two notes side-by-side. Redefine your energy, respecting a phrase’s real energy properties, and you’ll discover true legato and natural phrasing.

As a rule, every note is either in diminuendo, in crescendo or a pressure point {arrival point, Energy Pillar}. You’ll rarely get tired if you’re always going somewhere or coming from somewhere. You get tired when you’re directionless, like tagging behind your wife on a shopping trip. Static energy tires because of its lack of release and renewal. Oddly, although it’s generally less tiring to walk over flat terrain, in music it’s less tiring to walk over hilly terrain.

The reason for this is that when you give out emotional energy while remaining sensitive to it with listening eyes and open ears, it comes back to you intact, like a boomerang, and refreshing you. On the other hand, when you hold energy and expression inside, it quickly becomes blocked and produces all kinds of tension – physical, emotional and mental. And when you release energy expressively but don’t remain sensitive to it, you lose it forever and quickly become emotionally drained and physically tired. Why this should be remains a mystery.

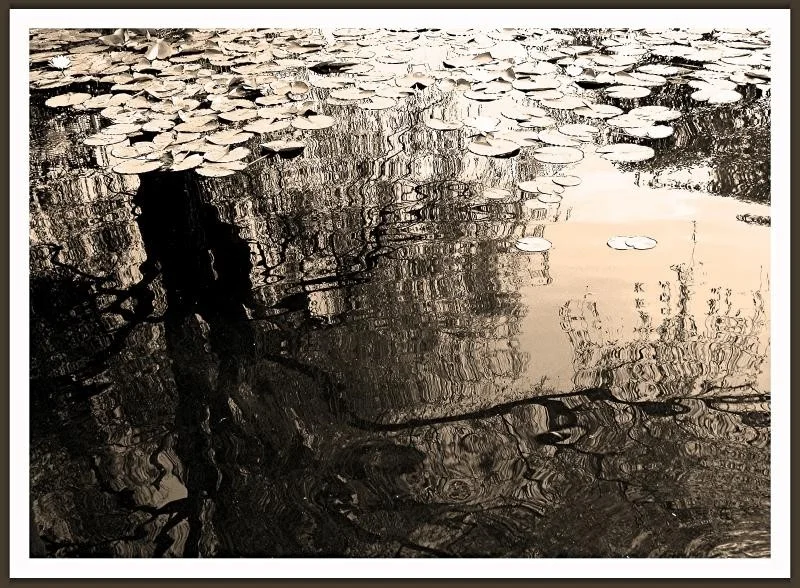

The reverse side also has a reverse side. – Japanese Proverb

You need release from tension whenever possible. Only in this way can the points of tension and expression be fully felt and realized. It’s important to be aware of every crescendo and diminuendo, no matter how small, in order to create a successful interpretation. In practice, the continual swells need to be exaggerated.

It may seem like an overstatement to say that every single note is either in crescendo, in diminuendo or an arrival point, but it’s not really. It would be more accurate of course to say that every note is either increasing in energy (tension), decreasing in energy, or a pressure point; after all, there are a lot of different ways to increase or decrease energy besides altering the volume. But in general, an increase in energy results in an increase in volume and vice-versa. {Occasionally the energy either moves forward into a pressure point in diminuendo, or arrives on it with a sudden decrease in volume (negative accent) to stunning effect, but this is the exception.}

As a rule it’s important to keep vision in crescendo and not be overly expressive in diminuendo. In crescendo, begin without an accent {or even with a negative accent} and keep gently feeding in new energy; in diminuendo, ride out the energy that has been released at the top of the phrase or the beginning of a diminuendo. You don’t have to deliberately let it deflate, but you needn’t push it or feed in new energy.

This is particularly difficult for singers and wind players to grasp at first because they need to sustain the breath to the end of the phrase. The concept of releasing energy sometimes seems to conflict with perceptions about proper breath support, but usually within a couple days, if not almost immediately, this is overcome. Tenors tend to be a caricature of “expressive sustaining” – they push every phrase all the way to the end, and as they come off it, slap you in the face with their lionesque masculinity.

The peak of every phrase or gesture should have an expressive accent that focuses into a single note { and within that note to a single split-second }. This is why I sometimes prefer the appellation pressure point to arrival point or Energy Pillar. They usually require expressive pressure: when placed at the right points, like acupuncture, they realign the energy to its original, natural state.

These notes should be looked forward to – save yourself for them emotionally and physically and they’ll be emotionally rewarding to play. Otherwise they’re effortful and the whole phrase becomes forced, belabored, or simply wandering. If you don’t release enough energy at a pressure point or if you miss it entirely, the following notes will tend to want to crescendo to compensate, or they’ll simply fall away in diminuendo and lose their presence.

Why is this? A good musician instinctively tries to balance negative and positive energy. He struggles to maintain emotional balance but doesn’t necessary know how to identify the emotional pressure points and organize them. When an Energy Pillar is miscalculated, the interpreter puts the energy elsewhere, generally over negative, unimportant space. This reverses the energy poles and the result is confusing to both interpreter and listener. The interpreter, at least, feels a certain satisfaction in achieving personal emotional balance between positive and negative energy; the listener either wonders what’s missing or accuses himself of not having understood the music. My very first conducting Guru as a teenager loved to chide his students: “It’s not your job to feel; it’s your job to make others feel!”

Technique and interpretation are linked much more intimately than generally realized. From my own studies, and from my experience teaching instrumentalists and coaching singers, clarifying direction in phrasing often solves a whole slew of technical and expressive problems. Mastering the flow of horizontal energy focuses the release of energy into key focal pressure points and sets all the rest of the notes in motion under their pull and influence. It does away with all static energy and defines the architecture of the piece, giving it greater meaning to the listener.

Undisciplined, unfocused, or misguided expression is tiresome and meaningless to the listener. You have to choose your moments (or rather become aware of them) and make them count. Then the rest falls into place. Don’t buy into the cheap gypsy mentality that improvisational expression is more valuable and true than planned-out expression { see Preparing for Performance below }.

As the emotional energy of an interpretation is defined logically, the physical energy follows, and countless technical problems disappear. Singers I coach, many of whom sing in the major Opera Houses of the world, often tell me that their technique improves more under my coaching than under the tutelage of their voice teachers. { In America, voice teachers generally teach “technique” and defer the “music” to vocal coaches. } Although I’ve studied much of the most-respected literature on vocal technique and have an outsider’s understanding of it, I’m not a singer and couldn’t possibly teach vocal technique beyond a beginner level.

I simply teach energy management – awareness and understanding of the movement of musical energy. Learn to manage your energy effectively and you may not need to think as much about “technique”.